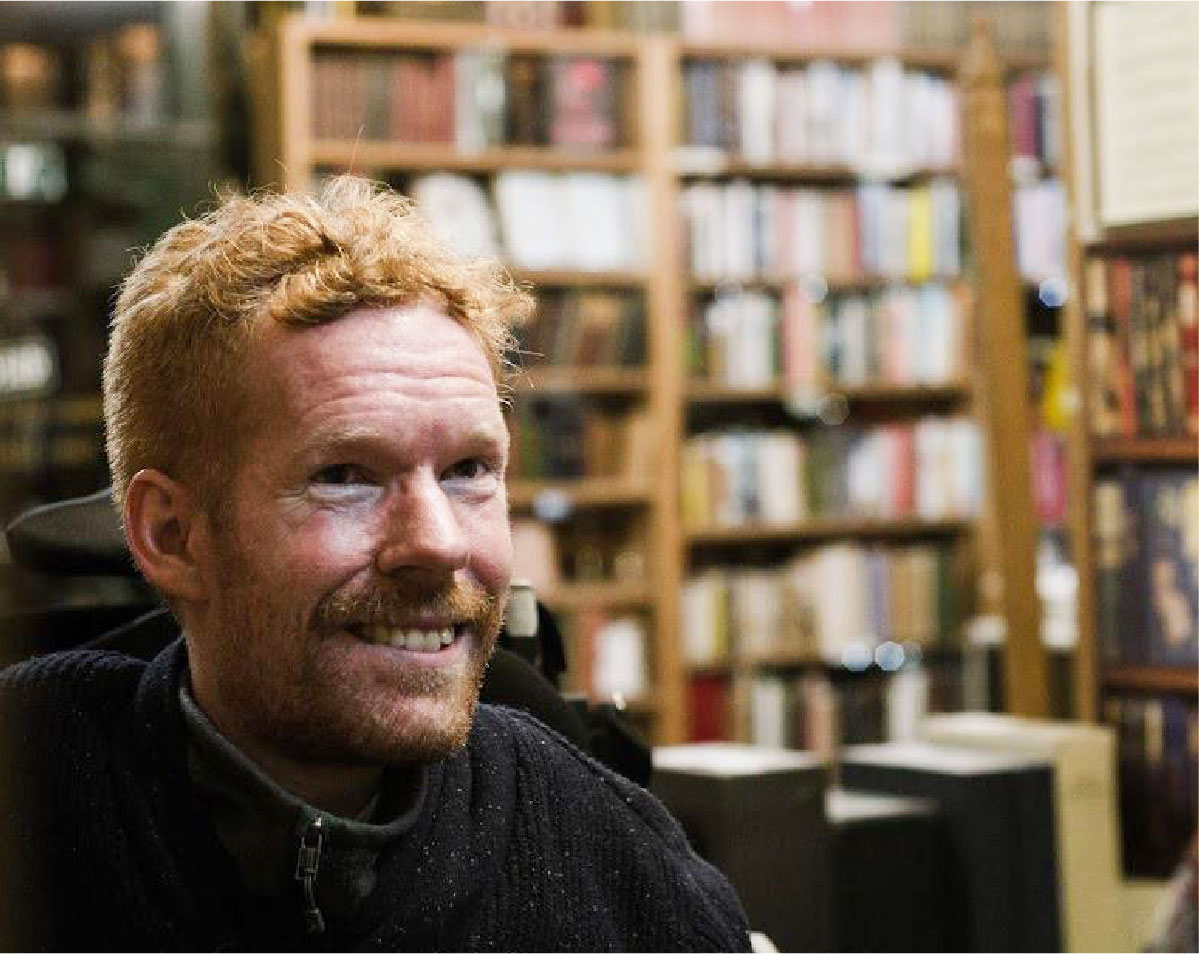

Friendships are funny things, aren’t they? We enjoy them and cry over them; we strive for them and wonder how they started; we watch them come and go, some passing quickly and others lasting a lifetime. I have been honored over the years to have a bounty of friends and, somewhere along the line, they started helping me with my caregiving needs. In fact, I can tell you where it started!

In high school, I played in a punk band, and the summer that we graduated, we hit the road on our first out-of-town tour. It was just a long weekend, and there was only room in the van (and our minds) for myself and my band mates, so they decided that they would take care of me. I still remember us all piling into a little bathroom, figuring it out together. And I think that’s how it had to happen for me: just some boys being boys, feeling invincible, acting dumb, and somehow landing on our feet.

“That was 16 years ago, and from there on out, it became just part of life and friendship.”

Nowadays, I have about 10 guys who rotate through getting me up in the mornings. None of them are medical professionals, none of them get paid to help. They’re all just pitching in to make my life happen because they’re my friends, they care about me, and I am their friend, I care about them. We are mutually pouring into each other’s lives, enriching one another and building one another up in love. As many of you know, this level of care fosters a sense of vulnerability on both sides and can create a deep bond, as well as profound weariness if the process isn’t managed well. The following are three tips on how to navigate the dynamics of friendship and caregiving for better results in both aspects of the relationship...

- Grace and Forgiveness: People make mistakes, and it’s no different when caregiving is involved. Be slow to anger and quick to assume the best of each other as you navigate these dynamics together.

- The Balancing Act: Make sure your friendship still has some space outside of caregiving. Have fun, hang out, go see a movie, eat some tacos! No one wants their association to be strictly centered around one giving the other a shower.

- Care Goes Both Ways: Always remember, you’re caring for one another. It’s a two-way street. No matter how asleep I am in the morning or how badly I need to use the restroom, I have to intentionally start each day by genuinely asking how my friend is doing and then going from there. You absolutely must communicate your needs with each other and prove trustworthy in your mutual responses of care.

“Friendship and caregiving are not mutually exclusive roles, and I’d even suggest that combining them can lead to wonderful experiences of depth and growth for all involved.”

It’s hard work, but worthy to be considered.