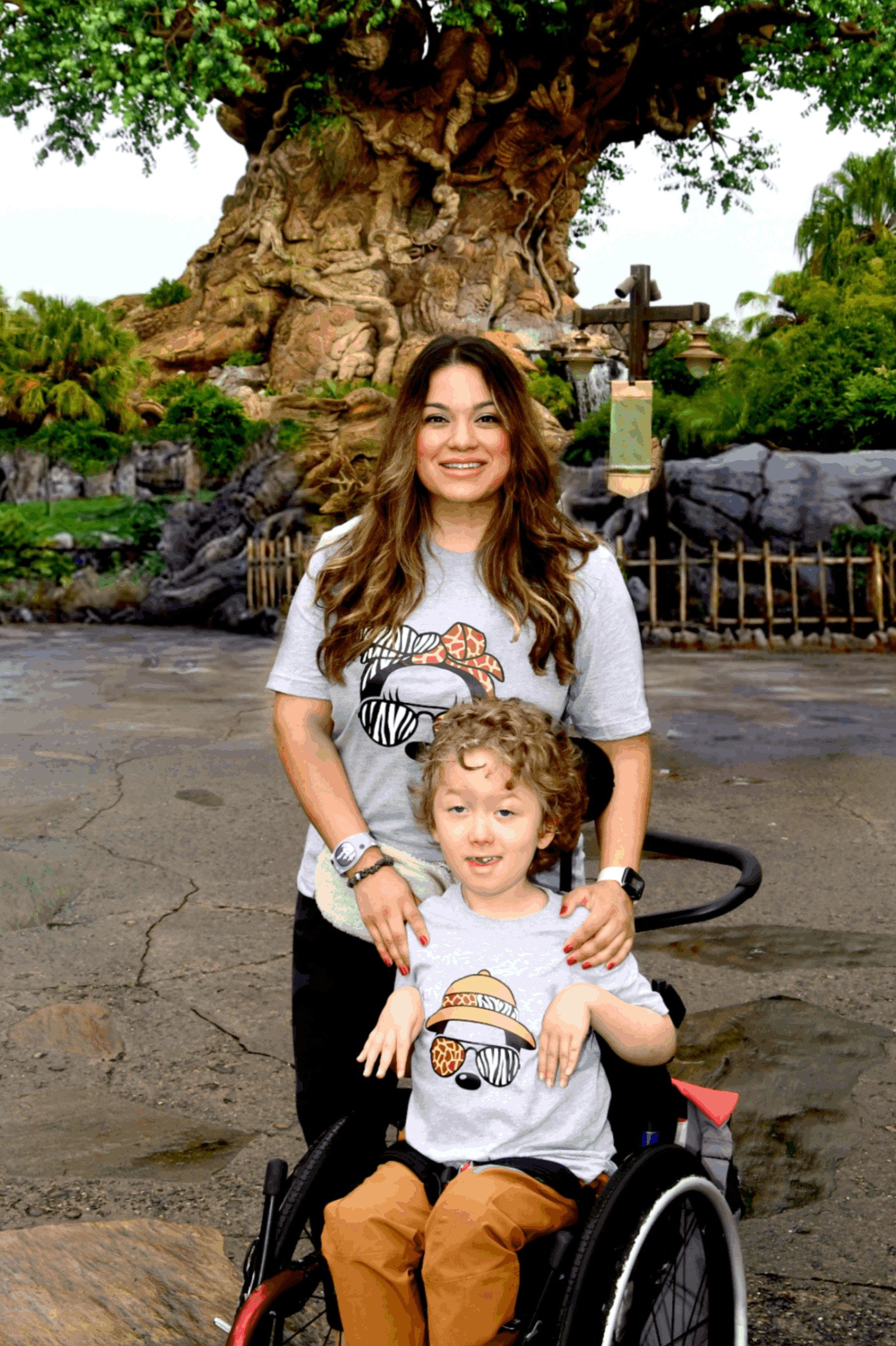

Brianna

Balancing a career with the demands of a rare disease

Getting an M.A. in mental health counseling was never part of the plan. I didn’t expect to fall in love with the profession my senior year of high school, but fall in love I did, all because I took an Advanced Placement class in psychology. I graduated college with a B.A. in psychology and every intention of becoming a therapist.

A Master’s degree was the next logical step; I couldn’t become a therapist without one. So I did the research and applied to a little-known university in suburban Indiana. My first few years in the program were blissful. I loved everything about it, from the coursework to the occasionally strange in-person assignments, like attending an open Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. I felt like I was doing something with my life. I felt like I was on the right track.

Then I learned more about what it takes to become a therapist.

It’s not just the coursework or the occasionally strange in-person assignments. It’s the years of supervised clinical work. It’s the examination and licensure and, above all, the long and thankless hours required to even think about becoming a therapist. As much as I loved counseling, I knew in my gut that my body would not be able to withstand the rigor of the profession.

I could burn myself out, but I had no guarantee the burnout would lead to anything but more health problems. I was faced with a choice: a career I loved or my wellbeing.

“It wasn’t an easy decision. But at the end of the day, I will always prioritize balance.”

It wasn’t an easy decision. But at the end of the day, I will always prioritize balance. My body can only handle so much. It might break my heart, but I would rather let go of things that do not serve me than push myself in the name of an idealized — and unrealistic — work ethic.

I can’t do everything I put my mind to. Not with SMA. And that’s okay. Success is just as much about knowing when to give up, and trusting that something even better is on the horizon.